A Barbarian in Hiroshima

The Shinkansen looks like a Boeing business jet stripped of wings and stretched long. The seats are wide with ample room to recline. A waitress dutifully attends to your car, passing out all manner of snack. The bathrooms have toilets that will wash your ass with a laser focused stream of water only to bathe you in warm air until dry. To feel uncivilized as an American in Japan is to be an Acela rider stepping onto a bullet train for the first time.

The ride from Osaka to Hiroshima takes exactly two hours and twenty-four minutes—within a forty second margin of error. Laura and I disembark from the train. It’s a sunny day in early spring, we exit the station to a hustle of activity: A baseball game recently let out and there is a weekend beer festival in full swing. We consult our phones for directions, orient ourselves, and begin walking along a wide boulevard. The city is modern, it glistens.

But of course, there are no old buildings in Hiroshima.

The first atomic bomb used in wartime was detonated six hundred meters above the dome of the Product Exhibition Hall, a building designed by the Czech architect Jan Letzel. It was completed in 1915, open to the public in 1921. In the aftermath of the blast the hall was the only structure left standing for miles. Its skeletal metal dome haunted the citizens of Hiroshima for years afterward, sparking a failed petition to knock it down. Instead, Peace Memorial Park was built in 1954, the “Bomb Dome” at its center. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

I catch a view of the building from the road. Dented steel ribs top a ruined structure in the distance, an arresting contrast to the manicured park and clean city surrounding it. My throat constricts a little and my eyes are a bit too wet. I blink and swallow. Laura and I walk up and read the plaques together. There are people on the sidewalk, volunteers educating visitors about the city’s existence before the bomb. They point to old pictures of the shopping district that once surrounded the area.

There’s an inescapable heaviness. Standing a hundred yards from the epicenter of the explosion, the atrocity becomes less abstract with a city milling around us. Collective guilt is a concept I never grasped intuitively before, but I do now.

Black and white photos of flattened buildings and debris are pinned to the fence around the dome building. My eyes shift between the ruins and the bustling park. The population of Hiroshima was 250,000 before the bomb. The city of Seattle was roughly the same size in 1945. There’s nothing for me to do with that information. My instinct to intellectualize past horror fails me as I stand there and I am left with tears on my cheeks; mourning people I don’t know, feeling shame for an act I didn’t commit.

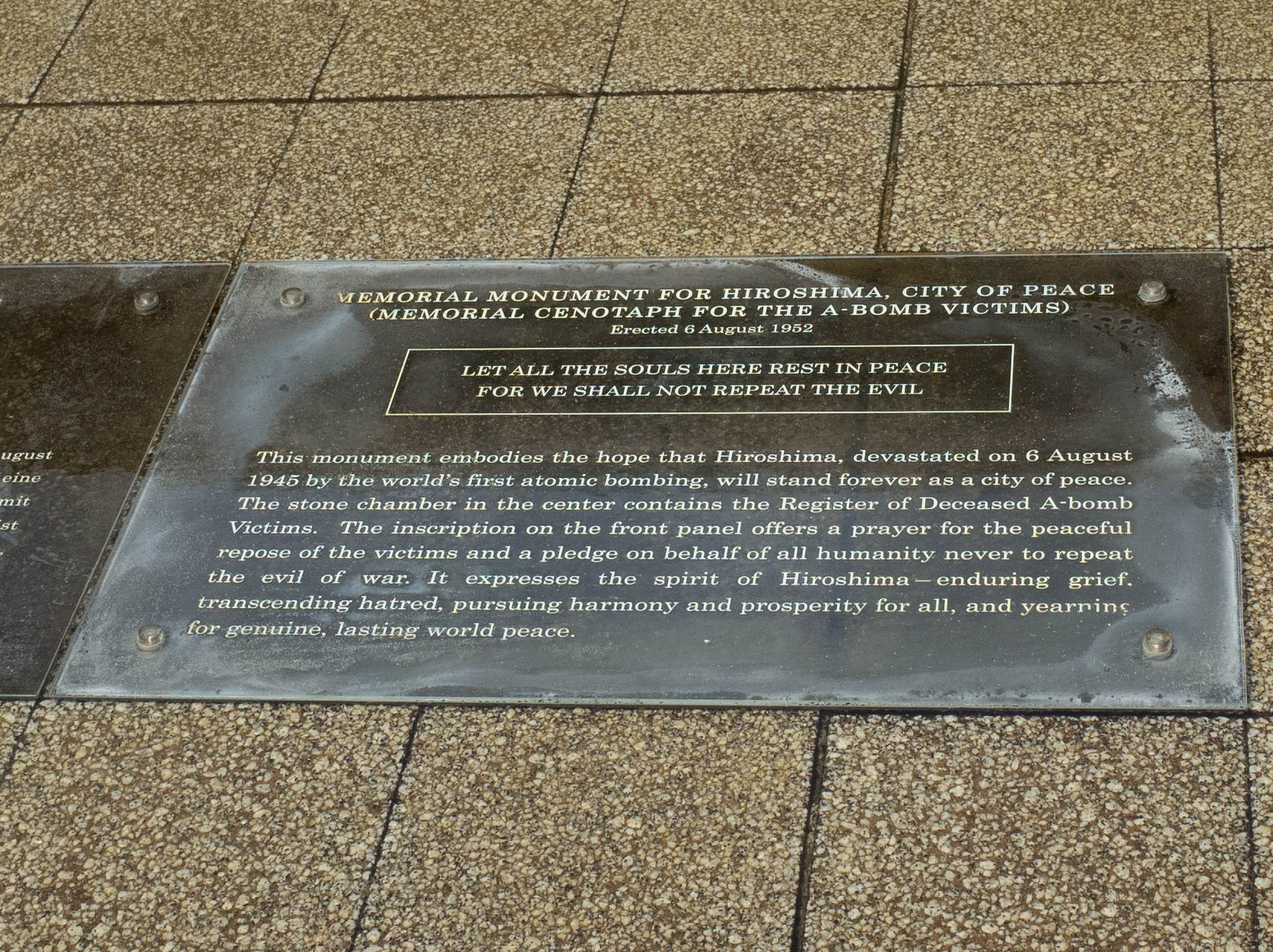

If any anger seethes under the surface, it is well hidden. Of course, given the Japanese talent for understatement, the gracious words written on these brass plaques could be a scathing reproach; something too subtle for my uncivilized eyes to detect.

Laura and I walk the rest of the way around the park as I chew on that thought. Japanese and American and European tourists are taking photos, paying respects. I am on my most self-conscious best behavior, keeping my head bowed. Nobody really cares, of course. We are all lost in our own reflection.

A covered shopping boulevard is nearby, filled with stores and restaurants and shoppers. Hunger is beginning to kick in and we still have to make it to Miyajima later that afternoon. We find a suitable oyster place—Hiroshima is known for oysters—and we sit down for a quick lunch. The restaurant is staffed by cheerful people in perfectly pressed outfits. They smile, patient with our stuttering guidebook Japanese.

Laura and I finish our meal. We walk to the bus, the free orange circle line which loops through Hiroshima’s tourist attractions. It’s full of westerners and is driven by a friendly gentleman in a blue uniform. The heaviness from earlier is lightened, more distant. By the time we board the ferry for Miyajima we are already thinking about the tame village deer.

The ferry glides into port, snapping in place like a button on a jacket. We walk up the gangway. The town square is small and perfectly appointed. Beneath the trees, deer stake out generous tourists. A girl is letting one lick her ice cream cone. We pause for a few snapshots before following the slender flagstone road to Itsukushima Shrine. The tide is low, so we won’t get the famous “floating” effect, but it’s worth the visit anyway.

Mudflats stretch out into the distance, scores of families are at work with clam shovels and buckets. Children are playing. Tourists with selfie-sticks are posing in front of the enormous shrine.

The most common topic of conversation between Laura and I while we are in Japan is our comparative lack of civilization. We share chuckles of embarrassment after inadvertently doing something rude only to be met with pleasant smiles. We stare in awe at the girl riding a bicycle through rainy streets that are so clean her white pants go unstained.

Not that I could ever live in a place like this. I enjoy being a barbarian too much. I’m a New Yorker: I prefer my cities dirty and loud; my crowds multicolored. A world where I could not yell obscenities at recalcitrant cab drivers would be a dreary place.

Despite all that, it’s hard not to be envious of Japan. A country that rose out of devastation, transforming from warriors to pacifists nearly overnight. A country whose national character is so strong that every small thing feels charged with purpose: The precisely hewn flagstones, the meticulously trimmed foliage; food prepared with as much care to presentation as to taste; a crime rate so low that the mere idea of criminality seems fantastical, like something that only happens in movies or overseas.

On the walk back to the boat I buy an ice cream bar. I eat half and let an approaching fawn finish the rest from my hand.

The last ferry leaves soon. We’ll get to Osaka in time for dinner, give or take forty seconds.